chapter 16 Geometry

GEOMETRY

GEOMETRY, LIKE the rest of mathematics, is abstract. In it the properties of the shapes and relative positions of things are studied. But we do not need to consider who is observing the things, or whether he becomes acquainted with them by sight or touch or hearing. In short, we ignore all particular sensations. Furthermore, particular things such as the Houses of Parliament, or the terrestrial globe are ignored. Every proposition refers to any things with such and such geometrical properties. Of course it helps our imagination to look at particular examples of spheres and cones and triangles and squares, But the propositions do not merely apply to the actual figures printed in the book, but to any such figures.

几何学和数学的其他分支一样,是抽象的。在几何学中,我们研究物体的形状特征以及它们之间的位置关系。但我们并不需要考虑是谁在观察这些物体,或者他是通过视觉、触觉还是听觉来认识它们。简而言之,我们忽略了一切具体的感官体验。 此外,诸如英国议会大厦或地球仪之类的具体事物也被忽略。每一个命题所指的,都是具有某些几何属性的任意事物。当然,观察具体的球体、圆锥体、三角形或正方形,有助于我们进行想象。但这些命题并不仅仅适用于书中印刷的那些具体图形,而是适用于所有具有这些几何特征的图形。

Thus geometry, like algebra, is dominated by the ideas of 'any' and

'some' things. Also, in the same way it studies the inter-relations of

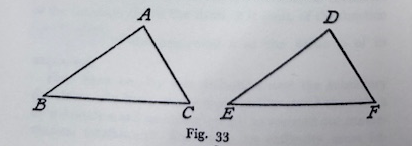

sets of things. For example, consider any two triangles

因此,几何学和代数学一样,受“任意事物”和“某些事物”这一类观念的支配。同样地,它也研究事物集合之间的相互关系。比如,设想任意两个三角形

What relations must exist between some of the parts of these triangles, in order that the triangles may be in all respects equal? This is one of the first investigations undertaken in all elementary geometries. It is a study of a certain set of possible correlations between the two triangles. The answer is that the triangles are in all respects equal, if: Either, (a) Two sides of the one and the included angle are respectively equal to two sides of the other and the included angle:

要使这些三角形在各方面都相等,它们的一些部分之间必须满足什么关系?这是所有基础几何中首先探讨的问题之一。它研究的是两个三角形之间某种可能对应关系的集合。答案是:如果满足以下任一条件,则这两个三角形在所有方面都相等:

- 一个三角形的两条边及其夹角,分别等于另一个三角形的两条边及其夹角。

Or, (b) Two angles of the one and the side joining them are respectively equal to two angles of the other and the side joining them:

或者,(b) 一个三角形的两个角及其夹边,分别等于另一个三角形的两个角及其夹边;

Or, (c) Three sides of the one are respectively equal to three sides of the other.

或者,(c) 一个三角形的三条边,分别等于另一个三角形的三条边。

This answer at once suggests a further inquiry. What is the nature of the correlation between the triangles when the three angles of the one are respectively equal to the three angles of the other? This further investigation leads us on to the whole theory of similarity (cf. Chapter 13), which is another type of correlation.

这个答案立刻引出了一个进一步的问题:当一个三角形的三个角分别等于另一个三角形的三个角时,这两个三角形之间的对应关系具有怎样的性质?这个进一步的探讨将我们引向整个相似形理论(参见第13章),这是一种不同类型的对应关系。

Again, to take another example, consider the internal structure of

the triangle

再举一个例子,考虑三角形

Also there is the still simpler correlation between the angles, of the triangle, namely, that their sum is equal to two right angles; and between the three sides, namely, that the sum of the lengths of any two is greater than the length of the third.

此外,三角形的角之间还存在一个更简单的对应关系,即它们的总和等于两个直角;而三条边之间的对应关系则是:任意两边的长度之和大于第三边的长度。

Thus the true method to study geometry is to think of interesting simple figures, such as the triangle, the parallelogram, and the circle, and to investigate the correlations between their various parts. The geometer has in his mind not a detached proposition, but a figure with its various parts mutually interdependent. Just as in algebra, they generalizes the triangle into the polygon, and the side into the conic section. Or, pursuing a converse route, he classifies triangles according as they are equilateral, isosceles, or scalene, and polygons according to their number of sides, and conic sections according as they are hyperbolas, ellipses, or parabolas.

因此,学习几何的真正方法是思考一些有趣而简单的图形,例如三角形、平行四边形和圆,并研究它们各个部分之间的对应关系。几何学家脑海中想的并不是孤立的命题,而是一个图形,其中各部分彼此相互依赖。正如在代数中一样,他将三角形推广为多边形,将边推广为二次曲线。或者,沿着相反的路径,他根据三角形是否为等边、等腰或不等边来分类,根据边的数量对多边形进行分类,根据是否为双曲线、椭圆或抛物线来分类二次曲线。

The preceding examples illustrate how the fundamental ideas of

geometry are exactly the same as those of algebra; except that algebra

deals with numbers and geometry with lines, angles, areas, and other

geometrical entities. This fundamental identity is one of the reasons

why so many geometrical truths can be put into an algebraic dress. Thus

if

前面的例子说明了几何的基本思想与代数的基本思想在本质上是完全相同的;只是代数处理的是数字,而几何处理的是线、角、面积以及其他几何对象。这种基本的一致性正是许多几何真理能够用代数形式表达出来的原因之一。因此,如果

and if

如果

But the parallelism between geometry and algebra can be pushed still further, owing to the fact that lengths, areas, volumes, and angles are all measurable; so that, for example, the size of any length can be determined by the number (not necessarily integral) of times which it contains come arbitrarily known unit, and similarly for areas, volumes, and angles. The trigonometrical formulae, given above, are examples of this fact. But it receives its crowning application in analytical geometry. This great subject is often misnamed as Analytical Conic Sections, thereby fixing attention on merely one of its subdivisions. It is as though the great science of Anthropology were named the Study of Noses, owing to the fact that noses are a prominent part of the human body.

但几何与代数之间的相似性还可以进一步推进,这要归功于一个事实:长度、面积、体积和角度都是可以度量的;也就是说,例如,任何一段长度的大小都可以通过它所包含的某个任意已知单位的数量(这个数量不一定是整数)来确定,面积、体积和角度也同理。前面提到的三角函数公式就是这一事实的例子。而这个思想的最高体现则是在解析几何中。这个伟大的学科常被误称为“解析二次曲线”,从而将人们的注意力仅局限于它的一个子领域。这就好比把伟大的“人类学”称作“鼻子研究”,仅仅因为鼻子是人体的一个显著部分。

Though the mathematical procedures in geometry and algebra are in essence identical and intertwined in their development, there is necessarily a fundamental distinction between the properties of space and the properties of number——in fact all the essential difference between space and number. The 'spaciness' of space and the 'numerosity' of number are essentially different things, and must be directly apprehended. None of the applications of algebra to geometry or of geometry to algebra go any step on the road to obliterate this vital distinction.

尽管几何和代数中的数学方法在本质上是相同的,并在发展过程中彼此交织,但空间的性质与数的性质之间仍存在一种根本的区别——实际上,这正体现了空间与数之间所有本质上的差异。空间的“空间性”(spaciness)与数字的“数性”(numerosity)是本质上不同的事物,必须通过直接的直觉来把握。代数在几何中的应用,或几何在代数中的应用,都丝毫不能消除这一重要的区别。

One very marked difference between space and number is that the former seems to be so much less abstract and fundamental that the latter. The number of the archangels can be counted just because they are things. When we once know that their names are Raphael, Gabriel, and Michael, and that these distinct names represent distinct beings, we know without further question that there are three of them. All the subtleties in the world about the nature of angelic existences cannot alter this fact, granting the premisses.

空间与数字之间一个非常显著的区别在于:空间似乎远不如数字那样抽象和根本。我们之所以能数出有多少位大天使,是因为它们是“存在的事物”。一旦我们知道他们的名字是拉斐尔(Raphael)、加百列(Gabriel)和米迦勒(Michael),而且这些不同的名字代表着不同的存在,那么我们便无需进一步推理就能知道:他们有三位。即使关于天使存在本质的讨论再复杂,也无法改变这个事实——前提既定,结论便不可更改。

But we are still quite in the dark as to their relation to space. Do they exist in space at all? Perhaps it is equally nonsense to say that they are here, or there, or anywhere, or everywhere. Their existence may simply have no relation to localities in space. Accordingly, while numbers must apply to all things, space need not do so.

但我们对它们与空间的关系却仍然一无所知。它们是否存在于空间之中?也许,说它们在这里、在那里、某处或无处,都是同样无意义的。它们的存在可能根本与空间中的位置无关。因此,尽管“数”必须适用于一切事物,“空间”却未必如此。

The perception of the locality of things would appear to accompany, or be involved in many, or all, of our sensations. It is independent of any particular sensation in the sense that it accompanies many sensations. But it is a special peculiarity of the things which we apprehend by our sensations. The direct apprehension of what we mean by the positions of things in respect to each other is a thing sui generis, just as are the apprehensions of sounds, colours, tastes, and smells. At first sight therefore it would appear that mathematics, on so far as it includes geometry in its scope, is not abstract in the sense in which abstractness is ascribed to it in Chapter 1.

我们对事物位置的感知似乎伴随着我们许多甚至全部的感官体验,或者说与之相关联。它独立于任何特定的感觉,正因为它能伴随多种感觉一起出现。但它又是我们通过感觉所把握的事物的一种特殊属性。我们直接把握事物彼此之间位置关系的能力,是一种独特的感知形式(sui generis),正如我们对声音、颜色、味道和气味的感知一样。因此乍一看,数学——至少在它包含几何的部分——似乎并不是第一章中所说的那种“抽象”的学问。

This, however, is a mistake; the truth being that the 'spaciness' of space does not enter into our geometrical reasoning at all. It enters into the geometrical intuitions of mathematicians in ways personal and peculiar to each individual. But what enter into the reasoning are merely certain properties of things in space, or of things forming space, which properties are completely abstract in the sense in which abstract was defined in Chapter 1; these properties do not involve any peculiar space-apprehension or space-intuition or space-sensation. They are on exactly the same basis as the mathematical properties of number. Thus the space-intuition which is so essential and aid to the study to geometry is logically irrelevant:

然而,这是一个错误;事实是,空间的“空间性”根本没有进入我们的几何推理之中。它以每个人都独特而个人化的方式进入了数学家的几何直觉。但真正进入推理的,只是空间中事物,或构成空间的事物的某些性质,而这些性质是完全抽象的,正如第一章中对“抽象”所作的定义那样;这些性质并不涉及任何特殊的空间感知、空间直觉或空间感受。它们与数的数学性质处于完全相同的逻辑基础上。因此,那种对学习几何非常重要、并能提供帮助的空间直觉,在逻辑上其实是无关紧要的。

It does not enter into the premisses when they are properly stated, nor into any step of the reasoning. It has the practical importance of an example, which is essential for the stimulation of our thoughts. Examples are equally necessary to stimulate our thoughts on number. When we think of 'two' or 'three' we see strokes in a row, or balls in a heap, or some other physical aggregation of particular things. The peculiarity of geometry is the fixity and overwhelming importance of the one particular example which occurs to our minds. The abstract logical form of the propositions when fully stated is, 'If any collections of things have such and such abstract properties, they also have such and such other abstract properties.' But what appears before the mind's eye is a collection of points, lines, surfaces, and volumes in the space: this example inevitably appears, and is the sole example which lends to the proposition its interest. However, for all its overwhelming importance, it is but an example.

它并不进入前提(如果前提被恰当地陈述),也不涉及推理的任何一步。它的实际重要性在于它作为一个例子的作用,而例子对于激发我们的思考是必不可少的。例子对于我们在思考“数”的时候同样是必要的。当我们想到“两”或“三”时,我们会在脑海中看到一排短划线、一堆球,或者其他某种具体事物的物理聚集。几何学的特殊之处在于:在我们头脑中浮现的那个特定例子具有固定性,并且极其重要。那些命题在被完整陈述时,其抽象的逻辑形式是:“如果某些事物的集合具有某些抽象性质,那么它们也将具有另外一些抽象性质。”但呈现在我们心眼中的,是空间中的点、线、面和体的集合:这个例子不可避免地出现,并且是唯一一个赋予命题其趣味性的例子。然而,尽管它如此重要,它终究只是一个例子。

Geometry, viewed as a mathematical science, is a division of the more general science of order. It may be called the science of dimensional order; the qualification 'dimensional' has been introduced because the limitations, which reduce it to only a part of the general science of order, are such as to produce the regular relations of straight lines to planes, and of planes to the whole of space.

几何学,作为一门数学科学,可以看作是更一般的“秩序科学”的一个分支。它可以被称为“维度秩序”的科学;之所以加上“维度”这一限定,是因为将其限定为“秩序科学”中一部分的那些限制,正是导致直线与平面之间、以及平面与整个空间之间产生规律性关系的原因。

It is easy to understand the practical importance of space in the formation of the scientific conception of an external physical world. On the one hand our space perceptions are intertwined in our various sensations and connect them together. We normally judge that we touch an object in the same place as we see it; and even in abnormal cases we touch it in the same space as we see it, and this is the real fundamental fact which ties together our various sensations. Accordingly, the space perceptions are in a sense the common part of our sensations. Again it happens that the abstract properties of space form a large part of whatever is of spatial interest. It is not too much to say that to every property of space there corresponds an abstract mathematical statement. To take the most unfavourable instance, a curve may have a special beauty of shape: but to this shape there will correspond some abstract mathematical properties which go with this shape and no others.

人们很容易理解“空间”在建立科学的外部物理世界观中的实际重要性。一方面,我们的空间感知与各种感觉交织在一起,并将它们彼此连接。我们通常会判断,我们触碰一个物体的位置与我们看到它的位置是相同的;即使在异常的情况下,我们触碰它的空间也与我们看到它的空间一致,而正是这个基本事实将我们各种感觉统一起来。因此,从某种意义上说,空间感知是我们各种感觉中的共同部分。再一次,空间的抽象属性构成了所有与空间相关之事物的重要组成部分。可以毫不夸张地说,空间的每一种属性都对应着某种抽象的数学命题。即使在最不具优势的情况下,比如一条曲线可能具有某种特殊的形状美感,这种形状也必然对应着一些抽象的数学属性,这些属性只与该形状相关,而与其他形状无关。

Thus to sum up: (1) the properties of space which are investigated in geometry, like those of number, are properties belonging to things as things, and without special reference to any particular mode of apprehension: (2) Space-perception accompanies our sensations, perhaps all of them, certainly many; but it does not seem to be a necessary quality of things that they should all exist in one space or in any space.

因此,总结起来:(1) 在几何学中研究的空间属性,像数字的属性一样,是属于事物本身的属性,且与任何特定的感知方式无关;(2) 空间感知伴随我们的感觉,可能是所有感觉,当然也包括许多感觉;但似乎并不是事物的必然属性,它们必须都存在于同一个空间中或某个空间中。