chapter 10 Conic Sections

CONIC SECTIONS

圆锥截面

WHEN THE Greek geometers had exhausted, as they thought, the more obvious and interesting properties of figure made up of straight line and circles, they turned to the study of other curves; and , with their almost infallible instinct for hitting upon things worth thinking about, they chiefly devoted themselves to conic sections, that is, to the curves in which planes would cut the surfaces of circular cones. The man who must have the credit of inventing the study is Menaechmus (born 375 B.C and died 325 B.C); he was a pupil of Plato and one of the tutors of Alexander the Great. Alexander, by and by, is a conspicuous example of the advantages of good tuition, for another of his tutors was the philosopher Aristotle. We may suspect that Alexander found Menaechmus rather a dull teacher, for it is related that he asked for the proofs to be made shorter. It was to this request that Menaechmus replied: 'In the country there are private and even royal roads, but in geometry there is only one road for all.' This reply no doubt was true enough in the sense in which it would have been immediately understood by Alexander. But if Menarchmus thought that his proofs could not be shortened, he was grievously mistaken; and most modern mathematicians would be horribly bored, if they were compelled to study the Greek proofs of the properties of conic sections. Nothing illustrates better the gain in power which is obtained by the introduction of relevant ideas into a science than to observe the progressive shortening of proofs which accompanies the growth of richness in idea. There is a certain type of mathematician who is always rather impatient at delaying over the ideas of a subject: he is anxious at once to get on to the proofs of 'important' problems. The history of the science is entirely against him. There are royal roads in science; but those who first tread them are men of genius and not kings.

当希腊几何学家们认为他们已经穷尽了由直线和圆构成的图形的更显而易见且有趣的性质时,他们转向了对其他曲线的研究;凭借他们几乎是无误的直觉,发现值得思考的事物,他们主要致力于圆锥截面的研究,也就是研究平面如何切割圆锥的表面。必须为发明这一研究领域的人归功于梅内克穆斯(公元前375年出生,公元前325年去世);他是柏拉图的学生,也是亚历山大大帝的导师之一。亚历山大大帝,逐渐地,成为了良好教育的显著例子,因为他另一个导师是哲学家亚里士多德。我们可以猜测亚历山大认为梅内克穆斯是一个比较乏味的老师,因为据说他要求证明过程缩短。梅内克穆斯对这一要求的回应是:“在乡村有私家路甚至王道,但在几何学中,所有人只能走一条路。” 这个回答无疑在亚历山大能立即理解的意义上是正确的。但如果梅内克穆斯认为他的证明无法简化,他就大错特错了;如果现代的数学家们被迫学习古希腊的圆锥曲线性质的证明,他们大概会觉得非常无聊。没有什么比观察到引入相关思想到科学中所获得的权力增长,更能说明科学进步的力量了,因为这种进步伴随着证明过程的逐步简化,而这一变化正是思想丰富度增长的结果。有一种类型的数学家总是对在学科思想上拖延感到不耐烦:他急切地想要继续推导“重要”问题的证明。科学的发展史完全与他相反;科学中确实有“王道”存在,但最先走上这些道路的不是国王,而是天才人物。

The way in which conic sections first presented themselves to

mathematicians was as follows: think of a cone (cf.Fig.15), whose vertex

(or point) is

圆锥曲线首次呈现给数学家的方式如下:想象一个圆锥(参见图15),其顶点(或点)为

For example, a conical shade to an electric light is often an example

of such a surface. Now let the 'generating' line which pass through

例如,电灯的圆锥形灯罩通常就是这样一个表面的例子。现在让“生成”线通过

(1)The plane may cut the cone in a closed oval curve, such as

The plane may be parallel to a tangent plane touching the cone along one of its 'generating' lines as for example the plane of the curve

in the diagram is parallel to the tangent plane touching the cone along the generating line ; the curve is still confined to one of the half-cones, but it is now not a closed oval curve, it goes on endlessly as long as the generating lines of the half-cone are produced away from the vertex. Such a conic section is called a parabola. The plane may cut both the half-cones, so that the complete curve consists of two detached portions, or 'branches' as they are called, this case is illustrated by the two branches

and which together make up the curve. Neither branch is closed, each of them spreading out endlessly as the two half-cones are prolonged away from the vertex. Such a conic section is called a hyperbola. 平面可能切割圆锥,形成一个封闭的椭圆曲线,例如

,它完全位于两个半圆锥中的一个上。在这种情况下,平面将根本不会与另一个半圆锥相交。这样的曲线叫做椭圆,它是一种椭圆形曲线。圆锥的这种切割的一个特殊情况是当平面垂直于 时,那么切割面,例如 或 ,将是一个圆。因此,圆是椭圆的一个特殊情况。 平面可能与一个切线平面平行,该切线平面沿着圆锥的某条“生成”线与圆锥相切,例如图中的曲线

所在的平面平行于沿生成线 与圆锥相切的切线平面;此时,曲线仍然局限于一个半圆锥内,但它不再是一个封闭的椭圆曲线,而是随着半圆锥的生成线从顶点远离时无休止地延展下去。这样的圆锥曲线被称为抛物线。 平面可能切割两个半圆锥,使得完整的曲线由两个分离的部分组成,或者称为“分支”,这种情况由两个分支

和 展示,这两个分支共同构成了这条曲线。没有一个分支是封闭的,每一个分支都随着两个半圆锥从顶点延伸而无休止地扩展开来。这样的圆锥曲线被称为双曲线。

There are accordingly three types of conic sections, namely, ellipses, parabolas, and hyperbolas. It is easy to see that, in a sense, parabolas are limiting cases lying between ellipses and hyperbolas. They form a more special sort and have to satisfy a more particular condition. These three names are apparently due to Apollonius of Perga (born about 260 B.C., and died about 200 B.C.), who wrote a systematic treatise on conic sections which remained the standard work till the sixteenth century.

因此,圆锥曲线有三种类型,即椭圆、抛物线和双曲线。很容易看出,从某种意义上说,抛物线是椭圆和双曲线之间的极限情况。它们形成了一种更特殊的类型,必须满足更具体的条件。这三个名称显然是由佩尔加的阿波罗尼乌斯(大约公元前260年出生,公元前200年左右去世)提出的,他写了一部关于圆锥曲线的系统性著作,这部著作一直是标准作品,直到十六世纪。

It must at once be apparent how awkward and difficult the

investigation of the properties of these curves must have been to the

Greek geometers. The curves are plane curves, and yet their

investigation involves the drawing in perspective of a solid figure.

Thus in the diagram given above we have practically drawn no subsidiary

lines and yet the figure is sufficiently complicated. The curves are

plane curves, and it seems obvious that we should be able to define them

without going beyond the plane into a solid figure. At the same time ,

just as in the 'solid' definition there is one uniform method of

definition —namely, the section of a cone by a plane—which yields three

cases, so in any 'plane' definition there also should be one uniform

method of procedure which falls into three cases. Their shapes when

drawn on their plane are those of the curved line in the three figures

16,17 and 18. The point

立刻就能看出,对于古希腊几何学家来说,研究这些曲线的性质是多么尴尬和困难。这些曲线是平面曲线,然而它们的研究却涉及到一个实心图形的透视绘制。因此,在上面给出的图示中,我们几乎没有绘制任何辅助线,然而图形却已经足够复杂。这些曲线是平面曲线,似乎显而易见,我们应该能够在不超出平面进入固体图形的情况下定义它们。与此同时,正如在“固体”定义中存在一个统一的定义方法——即通过平面切割圆锥——它产生了三种情况一样,在任何“平面”定义中也应该存在一个统一的过程方法,并且同样分为三种情况。当这些曲线被绘制在平面上时,它们的形状就是图16、17和18中的弯曲线。图中的点

.jpg)

In the diagrams 16 and 18, two points,

在图16和图18中,可以看到标出两个点

Finally 500 years later the last great Greek geometer, Pappus of

Alexandria, discovered the final secret which completed this line of

thought. In the diagrams 16 and 18 will be seen two lines,

最后,500年后,最后一位伟大的希腊几何学家,亚历山大的帕普斯,发现了完成这一思路的最终奥秘。在图16和图18中可以看到两条直线,

When Pappus had finished his investigations, he must have felt that, apart from minor extension, the subject was practically exhausted; and if he could have foreseen the history of science for more than a thousand years, it would have confirmed his belief. Yet in truth the really fruitful ideas in connexion with this branch of mathematics had not yet been even touched on, and no one had guessed their supremely important applications in nature. No more impressive warning can be given to those who would confine knowledge and research to what is apparently useful, than the reflection that conic sections were studied for eighteen hundred years merely as an abstract science, without a thought of any utility other than to satisfy the craving for knowledge on the part of mathematicians, and that then at the end of this long period of abstract study, they were found to be the necessary key with which to attain the knowledge of one of the most important laws of nature.

当帕普斯完成他的研究时,他一定觉得除了些许的扩展,这个学科几乎已经被穷尽了;如果他能预见到科学史上超过一千年的发展,他的信念就会得到验证。然而,事实上,与这门数学分支相关的真正富有成效的思想甚至还没有被触及,没人能猜到它们在自然界中的极其重要的应用。对于那些将知识和研究局限于显然有用的事物的人,再没有比以下的反思更为有力的警示:圆锥曲线被研究了1800年,仅仅作为一门抽象的科学,而没有考虑任何实际的用途,唯一的目的只是满足数学家们对知识的渴望;而且在这段漫长的抽象研究结束时,人们发现它们是揭示自然界最重要定律之一的关键。

Meanwhile the entirely distinct study of astronomy had been going forward. The great Greek astronomer Ptolemy (died A.D. 168) published his standard treatise on the subject in the University of Alexandria, explaining the apparent motions among the fixed starts of the sun and the planets by the conception of the earth at rest and the sun and the planets circling round it. During the next thirteen hundred years the number and the accuracy of the astronomical observations increased, with the result that the description of the motions of the planets on Ptolemy's hypothesis gad to be made more and more complicated. Copernicus (born A.D. 1473 and died A.D. 1543 ) pointed that the motions of these heavenly bodies could be explained in a simpler manner if the sun were supposed to rest, and the earth and planets were conceived as moving round it. However, he still thought of these motions as essentially circular though modified by a set of small corrections arbitrarily superimposed on the primary circular motions. So the matter stood when Kepler was born at Stuttgart in Germany in A.D. 1571. There were two sciences, that of the geometry of conic sections and that of astronomy, both of which had been studied from a remote antiquity without a suspicion of any connextion between the two. Kepler was an astronomer, but he was also an able geometer, and on the subject of conic sections had arrived at ideas in advance of his time. He is only one of many examples of the falsity of the idea that success in scientific research demands an exclusive absorption in one narrow line of study. Novel ideas are more apt to spring from an unusual assortment of knowledge— not necessarily from vast knowledge, but from a thorough conception of the methods and ideas of distinct lines of thought. It will be remembered that Charles Darwin was helped to arrive at his conception of the law of evolution by reading Malthus' famous Essay on Population , a work dealing with a different subject——at least, as it was the thought.

与此同时,天文学这一完全不同的学科也在不断发展。伟大的希腊天文学家托勒密(公元168年去世)在亚历山大城大学出版了他的天文学标准著作,解释了太阳和行星在固定星辰之间的表观运动,他提出地球是静止的,而太阳和行星围绕它旋转。在接下来的1300年里,天文观察的数量和精度不断增加,结果是,按照托勒密的假设,行星运动的描述变得越来越复杂。哥白尼(公元1473年出生,公元1543年去世)指出,如果假设太阳静止,而地球和行星围绕它运动,这些天体的运动可以通过更简单的方式来解释。然而,他仍然认为这些运动本质上是圆形的,尽管在主要的圆形运动上加入了一些小的修正,这些修正是随意叠加的。当开普勒于公元1571年出生在德国斯图加特时,天文学和圆锥曲线几何学这两门学科各自独立存在,且自古以来并未有人怀疑这两者之间有任何联系。开普勒是一位天文学家,但他也是一位能干的几何学家,在圆锥曲线的研究方面,他提出了超越时代的想法。他只是许多例子中的一个,证明了科学研究的成功并不要求对某一狭窄研究领域的专注。新颖的想法往往源于对知识的不同组合的深入理解——这不一定是庞大的知识量,而是对不同思维领域的方法和思想的透彻理解。将会被记住的是,查尔斯·达尔文通过阅读马尔萨斯的著名《人口论》一书,得以形成他对进化法则的理解,而这本书虽然讨论的是一个不同的主题——至少在当时是这样理解的。

Kepler enunciated three laws of planetary motion, the first two in 1609, and the third ten years later. They are as follows:

The orbits of the planets are ellipses, the sun being in the focus.

As a planet moves in its orbit, the radius vector from the sun to the planet sweeps out equal areas in equal times.

The squares of the periodic times of the several planets are proportional to the cubes of their major axes.

开普勒阐述了行星运动的三条定律,其中前两条定律在1609年提出,第三条定律则在十年后提出。它们如下:

行星的轨道是椭圆,太阳位于焦点处。

当行星在轨道上运动时,从太阳到行星的半径矢量在相等的时间内扫过相等的面积。

几个行星的周期时间的平方与它们的主轴的立方成正比。

These laws proved to be only a stage towards a more fundamental development of ideas. Newton (born A.D. 1642 and died A.D. 1727) conceived the idea of universal gravitation, namely, that any two pieces of matter attract each other with a force proportional to the product of their masses and inversely proportional to the square of their distance from each other. This sweeping general law, coupled with three laws of motion which he put into their final general shape, proved adequate to explain all astronomical phenomena, including Kepler's laws, and has formed the basic of modern physics. Among other things he proved that comets might move in very elongated ellipses, or in parabolas, or in hyperbolas, which are nearly parabolas. The comets which return——such as Halley's comet——must, of course, move in ellipses. But the essential step in the proof of the law of gravitation, and even in the suggestion of its initial conception, was the verification of Kepler's laws connecting the motions of the planets with the theory of conic sections.

这些定律被证明只是朝着更基本的思想发展迈出的一个阶段。牛顿(生于公元1642年,卒于公元1727年)提出了万有引力的概念,即任何两块物体之间相互吸引的力与它们的质量乘积成正比,与它们之间的距离的平方成反比。这个广泛的普遍定律,再加上他最终确立的三大运动定律,足以解释所有天文现象,包括开普勒定律,并为现代物理学奠定了基础。除此之外,他还证明了彗星可能沿着非常拉长的椭圆轨道、抛物线轨道或近似抛物线的双曲线轨道运动。那些会返回的彗星——比如哈雷彗星——当然必须沿椭圆轨道运动。但在引力定律证明的关键步骤中,甚至在它最初构思的建议中,验证开普勒定律将行星运动与圆锥曲线理论联系起来,起到了至关重要的作用。

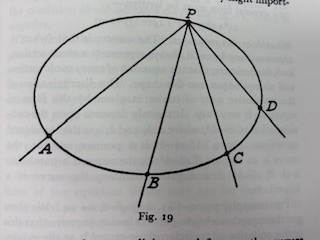

From the seventeenth century onwards the abstract theory of the

curves has shared in the double renaissance of geometry due to the

introduction of co-ordinate geometry and of projective geometry. In

projective geometry the fundamental ideas cluster round the

consideration of sets (or pencils, as they are called) of lines passing

through a common point (the vertex of the 'pencil'). Now (cf. Fig.19) if

从十七世纪起,曲线的抽象理论便参与了由于引入坐标几何和投影几何而带来的几何学的双重文艺复兴。在投影几何中,基本的思想围绕着考虑通过一个共同点(即“笔”顶点)相交的直线的集合(或称为“笔”)展开。现在(参见图19),如果

Finally, we come back to the point at which we left co-ordinate

geometry in the last chapter. We had asked what was the type of loci

corresponding to the general algebraic from

最终,我们回到上章中我们在坐标几何部分停下来的地方。我们曾经问过,形如

这表示什么?答案是(当它表示某个轨迹时)它总是表示一个圆锥截面,此外,任何圆锥截面的方程总是可以被转换成这种形式。通过这种方程形式来区分特定种类的圆锥曲线是非常容易的。它完全取决于对

For example, put

例如,令

因此,所谓的二次项可以被写成一个完全平方的形式。展开平方后,我们得到:

因此,通过比较,可以得出

The limitation, introduced by saying that , when the general

equation represents any locus, it represents a conic section, is

necessary, because some particular cases of the general equation

represent no real locus. For example

这一限制——即“当一般方程表示某个轨迹时,它表示一个圆锥截面”——是必要的,因为一般方程的某些特殊情况并不表示任何实际的轨迹。例如,方程

Some exceptional cases are included in the general form of the

equation which may not be immediately recognized as conic sections. By

properly choosing the constants the equation can be made to represent

two straight lines. Now two intersection straight lines may fairly be

said to come under the Greek idea of a conic section. For, by referring

to the picture of the double cone above, it will be seen that some

planes through the vertex,

一些特殊情况被包含在方程的一般形式中,这些情况可能不会立即被识别为圆锥曲线。通过适当选择常数,该方程可以变为表示两条直线。现在,可以合理地认为两条交叉直线属于古希腊对圆锥曲线的定义。因为,参照上面双锥体的图示,可以看到,某些穿过顶点